The Farmhouse in Tuscany

I recently visited a wonderful old farmhouse in the hills above Lucca. From the historical land maps I was able to observe that the footprint of the building has remained unaltered for the past 200 years. I was truly intrigued as I imagined the careful thought that had gone into locating this house such a long time ago. The house was gently ventilated with pleasant evening breezes and south facing (mezzogiorno) to maximize the energy of the sun. It was raised up on the hillside just enough to enjoy the dryer and healthier air above the dampness and thick fog that lingered in the river valley below. The house was protected from the cold north winds with the mountains to the rear, and a few trees were strategically located as wind breaks.

The farmhouse in question had many of the qualities that I read about in a celebrated book called Delle case de’ contadini (farmers’ houses) written by Ferdinando Morozzi in 1770. Morozzi was an engineer based in Florence who wrote a practical manual for building farmhouses. His recommendations were based on 20 years of observations throughout the length and breadth of Tuscany.

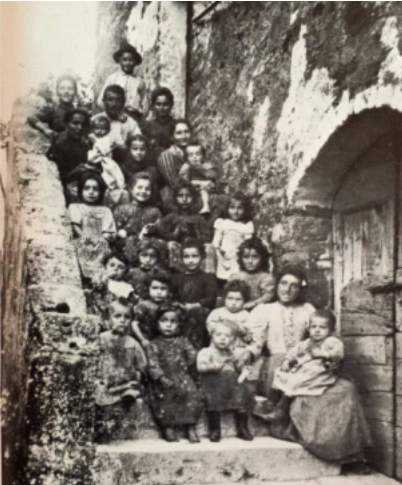

The living quarters of the farmhouse were located upstairs where rising damp was unable to leave its mark. The lower floors were used for animals, generating lots of natural heat during the cold winter months. The remaining cellars provided the cooler atmosphere to cure ham, keep olive oil or store wine. The farmhouse had an external south-facing staircase. The exposure to the sun would stop slippery moss forming and avoid harsh northerly winds when the farmer got out of his warm bed during the night to tend to the animals. Unlike in towns and villages, such staircases were preferably located outdoors, keeping dirt out of the house. A void under the external steps was considered the perfect place for fattening a pig!

Only after careful consideration did the farmer undertake this important initiative of building the farmhouse with his own hands, perhaps with the guidance of a more experienced mason. This is in stark contrast to nowadays where houses are mindlessly located at the bottom of damp valleys to satisfy local zoning policies, or facing the main road with little or no criteria.

The working farm in Tuscany was a collage of elements based on necessity, a shoestring budget and lots of hard work. Nothing was left to chance. One of the first considerations to determine the suitability of the location was good air quality. This was followed by the availability of water, with a well (il pozzo) located nearby or a buried cistern that could catch run-off from the roof. We frequently see a number of add-ons capped by changes in roof height. This was a result of the family growing or the farm expanding over time, adding both character and a sense of history to the building. The wood-burning oven (il forno) that prospective buyers may incorrectly refer to as a “pizza oven” was a fundamental piece of equipment usually large enough to make at least 3 loaves of bread given the effort involved in heating it up. Afterwards, the residual heat would be used for other tasks such as the drying of figs.

Whenever possible, to avoid risk of fire, the haybarn was built to stand alone. The upper floor had a ventilated wall or mandolata that was normally protected from the southerly wind known as lo Scirocco, which brought unwanted humidity to the dry hay. The barn was accessed using a long ladder through a tall arched opening on the upper floor. The ground floor was used for farm equipment and carts. The chestnut harvest in November was slowly dried for several weeks in the chestnut dryer, locally known as a metato. A covered area or porticato was necessary for getting outdoor jobs done during rainy days, whilst the pergolato provided plenty of shade during the hot summer days. A paved area in stone or terracotta known as the aia was the space in front of the farmhouse used for thrashing corn.

The most important room of the house was the kitchen, dominated by a large open fireplace which became the natural gathering space for the entire family. The size of the kitchen and kitchen table were proportional to the size of the farm (podere). One of the more unusual pieces of furniture was referred to as la madia. This was a sort of chest or trough used for preparing and kneading the dough for bread or pasta.

Sadly, there are very few working farms left in the hillsides of Tuscany. The surrounding land that was once so scrupulously cared for is now in an advanced state of neglect. The hardships of this simple farming life eventually stimulated widespread emigration in the 1900s. The irony of it all is that many of these sought-after farmhouses are now owned by non-Italians who want the house but not the farm. Maybe there is a responsibility on the new owners to understand, appreciate and respect the history that goes with these beautiful farmhouses. After all, society has gone full circle, with the fashionable concepts of organic food, carbon footprints, slow food and farmer’s markets, so perhaps an important contribution can be made simply by working the land!

0 comments

Write a comment